Public speaking, an age-old practice of conveying messages, ideas, or emotions to a large audience, has been an integral aspect of human civilization.

From the great rhetoricians of ancient Greece to the influential speakers of today, the ability to speak convincingly in public settings has been valued and nurtured over millennia.

In tech, public speaking emerges as a surprisingly crucial skill.

The ability to communicate effectively enhances the clarity of project discussions, facilitates smoother collaboration, and ensures that complex technical concepts are understood by a variety of audiences, including those without a technical background.

I'd honestly say it's essential not only in presenting and explaining your work but also in advocating for new ideas and technologies.

It plays a significant role during team meetings, technical reviews, and in the process of securing stakeholder buy-in on projects.

As you progress in your careers, especially when moving into leadership positions, public speaking skills becomes increasingly important. These skills are critical for motivating teams, articulating project visions, and communicating milestones to non-technical stakeholders.

The digital era also presents numerous opportunities for software engineers to share their expertise wider, through platforms such as technical blogs, online tutorials, and webinars.

Additionally, community engagement - through tech meetups, conferences, and workshops - requires the ability to convey technical knowledge in an engaging manner. Such interactions can not only bolster your professional network but also contribute to the collective knowledge of the tech community.

This articles delves into the rich history, techniques, and practices that have shaped the art of public speaking, hopefully offering some valuable insights for those aspiring to improve in all of the above!

A Brief History of Public Speaking

The roots of public speaking can be traced back to ancient civilizations. In Ancient Greece, oratory was an esteemed skill, essential in politics and public life.

Iconic figures like Demosthenes practiced speaking with pebbles in his mouth to improve his articulation, highlighting the lengths orators went to refine their skills.

Greek philosophers such as Aristotle laid the foundation for rhetoric, which is the art of persuasion, and has influenced the structure and style of public speaking to this day.[1]

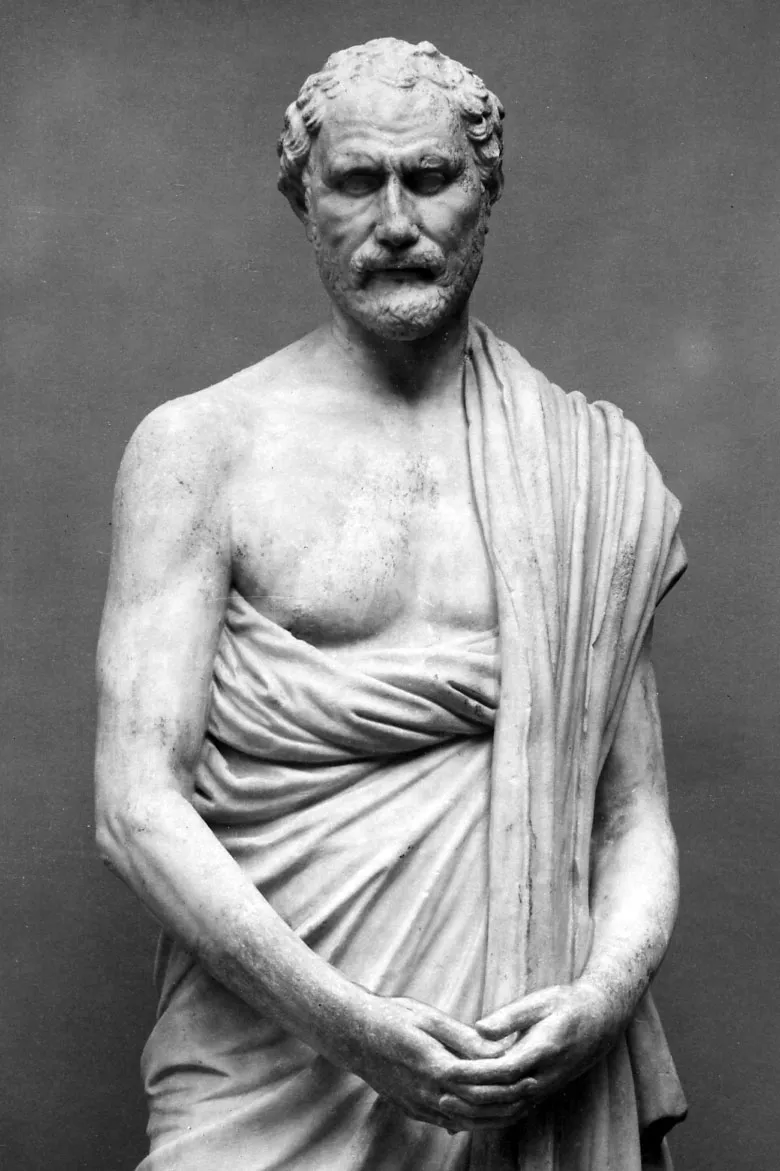

Demosthenes (384–322 BC), considered one of the greatest orators in ancient Greece, is renowned for his "Philippics," a series of fiery speeches warning against the rise of Philip II of Macedon, the father of Alexander the Great. (2)

Despite being a great orator, Demosthenes actually had to over a speech impediment!

And one of the most frequently recounted tales involves him practicing his speeches with pebbles in his mouth.

This exercise was believed to strengthen his articulation. Furthermore, he would often practice by the seashore, striving to project his voice over the sound of the crashing waves, thereby developing his vocal strength.

Before reaching the status of statesman, he was a logographer, which meant he wrote speeches for judges and politicians. This steeped him in Athenian law and politics.

Despite his formidable eloquence, his staunch opposition to powerful figures led to a tragic end: fleeing retribution from Alexander the Great's regents, he took his own life.

Marble statue of Demosthenes, a Roman reproduction of a Greek original circa 280 BCE, housed in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen.

During the Roman Empire, orators like Cicero furthered the art of eloquence, elevating the standards for effective public discourse.

The Roman forums served as platforms for open debates, discussions, and declamations, reinforcing the societal importance of articulate communication.

You find yourself standing in the heart of the Roman Forum, the sun casting long shadows between majestic pillars. As you ascend the grand rostrum, the murmurs of the gathered crowd fade, and all eyes turn to you. The weight of history bears down, and echoes of great orators past seem to whisper in your ear. With the vast panorama of Rome spread out before you and the attentive masses hanging on your every word, you take a deep breath and deliver a speech that will resound through the annals of time.

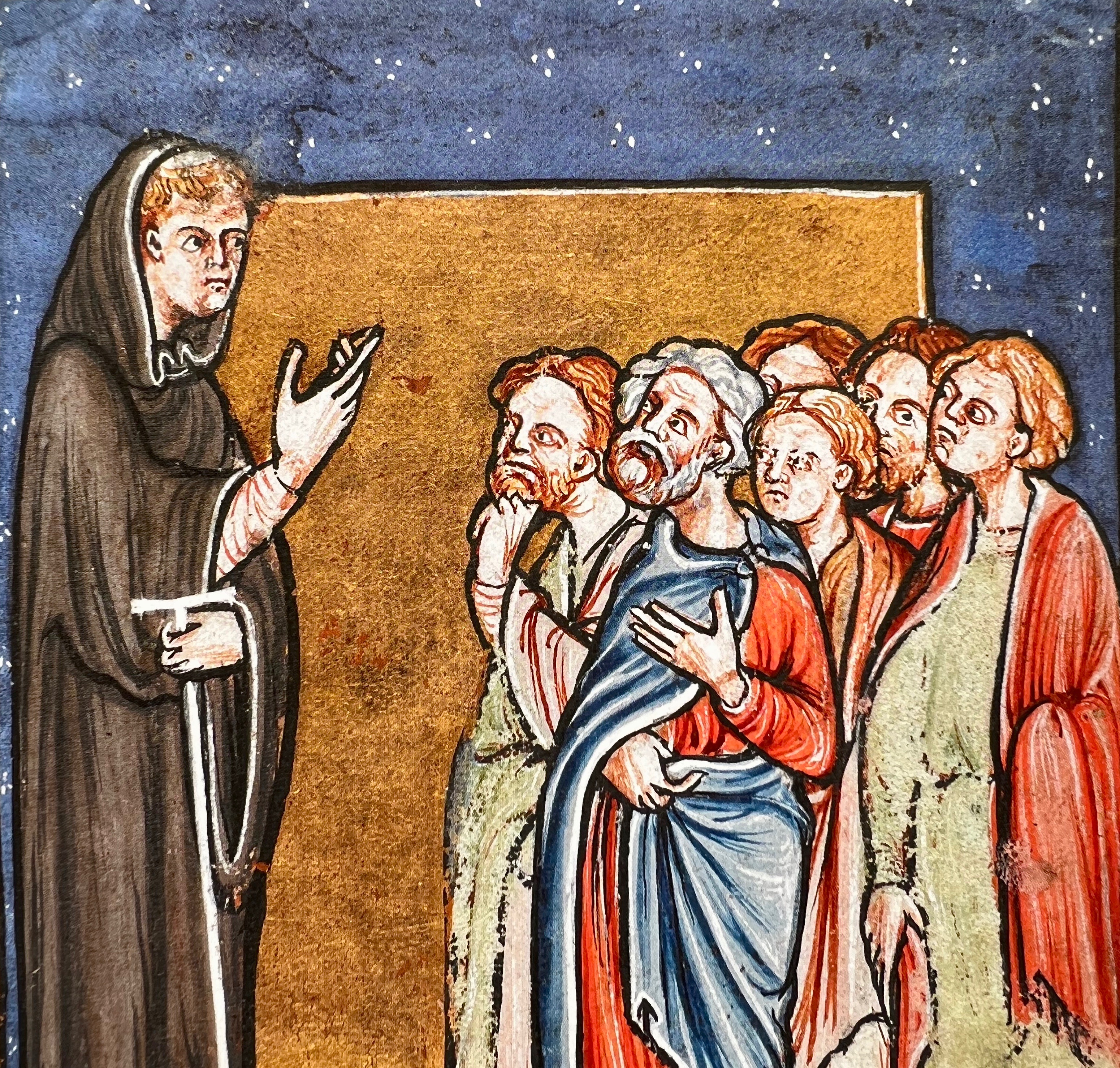

The Middle Ages saw the Church dominate public speaking, with sermons becoming the primary form of oral communication. Monastic schools and universities became centers for rhetorical studies, ensuring the continued importance of articulate communication.[3]

St. Cuthbert delivering a sermon to the Northumbrians (late 12th-century depiction in Bede’s life of St. Cuthbert).

St. Cuthbert delivering a sermon to the Northumbrians (late 12th-century depiction in Bede’s life of St. Cuthbert).

The Renaissance revitalized interest in classical rhetoric, laying the foundation for the modern principles of public speaking.

By the 19th and 20th centuries, the rise of democracy, education, and mass media transformed public speaking into a tool for social change, exemplified by speakers like Martin Luther King Jr. and Winston Churchill.

Barack Obama: The 44th President of the United States is known for his powerful and inspirational speeches. His oratory skills are characterized by a calm demeanor, deliberate pacing, and the ability to convey complex issues with emotional resonance. Obama's speeches, such as the one he delivered after winning the Nobel Peace Prize or his address after the Charleston church shooting, demonstrate his talent for blending the personal with the political.

Techniques and Tips for Mastering Public Speaking

The art of public speaking is not just about conveying information; it's about influencing, inspiring, and making an unforgettable impact on your audience.

I soon found out how important that was when becoming a coding Bootcamp Educator and needing to captivate my students during lectures that extend for up to two hours a time.

I wasn't always that great at it too! And had to really work on elevating my speaking prowess.

I quickly found that effective public speaking can be nurtured and cultivated with the right techniques and diligent practice.

Below are some insights I've found along the way.

Know Your Audience

Understanding your audience is the cornerstone of effective communication. Before drafting your speech, research who will be listening.

- What are their interests, demographics, cultural backgrounds, and expectations?

- By tailoring your message to resonate with them, you ensure relevance and engagement.

For instance, a technical subject presented to experts would differ in depth and jargon from one presented to novices.

I'm an Educator at a coding bootcamp and when I teach newcomers to coding—a realm often seen as complex and intimidating—I tailor my approach to their novice perspective.

Instead of diving straight into jargon and technicalities, I lean heavily on metaphors, drawing parallels between everyday experiences and programming concepts.

This helps bridge the gap between the familiar and the unknown, making the learning curve smoother. By using relatable analogies and clear, straightforward language, I've found that students grasp intricate coding principles more easily.

This is why it's important to know and adapt to your audience: by meeting them where they are, you can make even the most complex topics accessible and engaging.

Crafting Compelling Speeches: The Ethos, Pathos, Logos Framework

A well-organized speech is easier to deliver and more digestible for the audience.

- Begin with an introduction that grabs attention - this could be a startling fact, a poignant quote, or a compelling anecdote.

- Clearly state your main points and organize them logically.

- Each point should be substantiated with evidence, be it statistics, anecdotes, or expert opinions.

In Aristotle's seminal work, "Rhetoric," he proposes a triad of ethos, pathos, and logos as central to classical rhetoric and the art of persuasion.

Here's what they mean:

- Ethos (Credibility): Ethos pertains to the speaker's character, credibility, and reputation. Aristotle believed that if an audience perceives the speaker as credible and morally sound, they are more inclined to be persuaded.

In today's digital age, ethos is reflected in personal branding, qualifications, testimonials, and endorsements. For instance, a doctor discussing medical topics would naturally have more ethos in that realm than someone without medical training.

- Pathos (Emotion): Pathos revolves around appealing to the audience's emotions, values, and desires. By resonating with the listeners' feelings and aspirations, the speaker can create a bond and instill a sense of urgency or empathy.

Modern advertisers frequently employ pathos. Commercials might depict heartwarming family moments, exhilarating adventures, or narratives of personal triumph, all designed to evoke specific emotions and associate these feelings with the product or service being promoted.

- Logos (Logic): Logos concerns the use of logic, reason, and evidence. A well-structured argument, supported by concrete evidence, facts, and logical sequencing, is more likely to convince the audience of its validity.

Academic papers, scientific reports, and judicial arguments heavily rely on logos. They present hypotheses or claims, back them with data or precedents, and use logical reasoning to arrive at conclusions. While "Rhetoric" was written in the 4th century BC, its principles, especially the ethos-pathos-logos triad, remain foundational in communication, public speaking, and persuasive writing. This is because these three pillars address the holistic nature of human cognition and decision-making. Ethos appeals to our trust in authority or expertise, pathos speaks to our human emotions and shared experiences, and logos satisfies our rational mind's need for structure and evidence.

In contemporary contexts, from political speeches to marketing campaigns, the most compelling messages often skillfully interweave all three elements. For instance, a politician might share a personal anecdote (pathos), cite economic data (logos), and highlight their years of service (ethos) in a single speech to persuade voters.

Consider how this might apply to a software engineer's impact in various settings:

Ethos: When interviewing or networking, start by highlighting your background and achievements in software development, such as significant projects you've contributed to or innovative solutions you've developed. Mentioning a successful project where your technical decision led to a marked improvement in performance or user experience can establish your credibility as an expert in your field.

Pathos: Don't forget to share a relatable experience of overcoming a challenging bug or the satisfaction of seeing your code come to life in a product used by many. This personal touch not only humanizes you but also creates an emotional connection with your audience, whether they are fellow developers, stakeholders, or non-technical listeners. It illustrates the passion and dedication behind the code, making your message more engaging and impactful.

Logos: When presenting a new tool, framework, or methodology, delve into the technical specifics—how it works, its benefits over existing solutions, and real-world applications. Include data, benchmarks, or case studies to support your points. This logical and evidence-based approach strengthens your argument and demonstrates a deep understanding of the subject matter, thereby enhancing your persuasiveness and the audience's trust in your expertise.

Don't forget to conclude your speech by reinforcing your main points and leaving the audience with a memorable takeaway or call to action.

Practice Makes Perfect

Even the most experienced speakers rehearse their speeches.

Practicing helps in refining content, perfecting delivery, and anticipating questions. Record your rehearsals to critique your tone, pacing, and body language. This repetitive process helps in internalizing the content, which allows for a more natural delivery.

Here are some actionable points to help guide your efforts:

Write and Rehearse: Before delivering, script your speech or at least outline the key points. Familiarize yourself with the content through repeated readings, ensuring you comprehend and internalize the message.

Mirror Practice: Stand in front of a mirror and speak. This allows you to observe facial expressions, gestures, and posture, refining them as you go.

Record and Review: Use your phone or camera to record your speeches. Playback helps in identifying areas of improvement, be it pacing, intonation, or non-verbal cues.

Feedback Loop: Present your speech to friends, family, or colleagues and actively seek feedback. They might offer insights or perspectives you hadn't considered.

Join Speaking Clubs: Organizations like Toastmasters offer a supportive environment to practice public speaking and receive constructive critiques.

Engage in Impromptu Speaking: Set aside times where you pick a random topic and speak on it for a few minutes. This enhances your ability to think on your feet.

Practice Breath Control: Engage in exercises that improve your breath control, ensuring a steady voice and aiding in stress reduction. Yoga and meditation can be beneficial in this aspect.

Vocal Warm-Ups: Just as singers warm up their voices, so should speakers. Humming, tongue twisters, and vocal stretching exercises can prevent strain and improve clarity.

Stay Updated: The best speakers are knowledgeable. Regularly read up on current events and diverse topics to build a vast reservoir of content to draw from.

Embrace Mistakes: Instead of fearing errors, view them as learning opportunities. After each presentation, reflect on what went well and what could be improved.

Engage with Visuals and Stories: Humans are visual creatures, and a well-designed slide or a pertinent image can significantly augment your message. Visual aids, however, should be used judiciously—avoid clutter and ensure that they complement your spoken words.

Beyond visuals, the power of storytelling cannot be overstated. Narratives captivate, make abstract concepts tangible, and foster empathy. Weaving personal stories or relevant anecdotes adds depth to your presentation and makes it relatable.

Mastering Delivery

Your voice and body are the primary tools in public speaking. Varying your pitch and tone keeps the audience engaged, while a controlled pace ensures comprehension.

Avoid monotonous delivery - instead, use emphasis and pauses strategically. Pausing can underscore a point, allow the audience to ponder, or give you a moment to collect your thoughts.

Non-verbal cues, like eye contact, facial expressions, and gestures, play a pivotal role in connecting with the audience. Being mindful of your posture and movements conveys confidence and authority.

Overcoming Stage Fright

It's common to experience jitters before facing an audience.

Recognizing that this anxiety is natural and often a sign of adrenaline can be comforting.

Techniques like deep breathing, grounding exercises, and positive affirmations can mitigate nerves.

Visualization, where one imagines a successful performance, can be a potent tool. Preparing for contingencies, such as technical glitches, can also instill confidence.

Lastly, engaging with the audience before the speech, perhaps through light conversation, can humanize them and alleviate the feeling of addressing a faceless crowd.

Some Thoughts from Me

Public speaking is more than an art; it's a powerful medium that has shaped civilizations, swayed public opinion, and transformed lives.

As you've seen in this article, the journey from the amphitheaters of Athens to the our current digital era underscores the enduring importance of effective and eloquent communication.

For those who aspire to master this craft, it is essential to understand its history, appreciate its evolution, and relentlessly hone one's skills..

...and as with any art, passion, persistence, and practice are the cornerstones of mastery in public speaking.

Get out there and talk to everyone. Talk to folks at meet ups. Raise your voice in group meetings.

Each speech, each audience, and each setting brings unique challenges and lessons.

With passion and perseverance, one can not only master the art of public speaking but also experience the profound joy of connecting with people and making a lasting impact.

Footnotes

References:

1 Aristotle. (1991). On rhetoric: A theory of civic discourse. Oxford University Press. 2. Demosthenes. (c. 351 BC). Philippics. 3. Murphy, J. (1994). Rhetoric in the Middle Ages: A history of rhetorical theory from Saint Augustine to the Renaissance. University of California Press. 4. Lucas, S. E. (2012). The art of public speaking. McGraw-Hill.